When you think of BIG sea creatures, you probably imagine great white sharks, huge blue whales, or ginormous cephalopods like the giant squid (or, for the more imaginative, the Kraken!). But would you believe me if I told you that the ocean is also home to a reptile that grows far larger than a human? Many people are familiar with the “typical” green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) or even the hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), known for its beautifully patterned shell. However, these species are dwarfed in size compared to the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Adult leatherback sea turtles are usually 6 to 8 feet long and 550 to 1500 pounds. To put that into context, imagine 3 to 8 adult men of average height and weight huddled together or 8 to 24 Labrador retriever dogs playing about in a group (now THAT would be heavenly!). An animal that big takes up a great deal of room, which is fine in the expansive ocean but is rather problematic if such a turtle is to become a museum research specimen. That is exactly the case with CM 44460, the famous leatherback sea turtle housed in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Section of Amphibians and Reptiles.

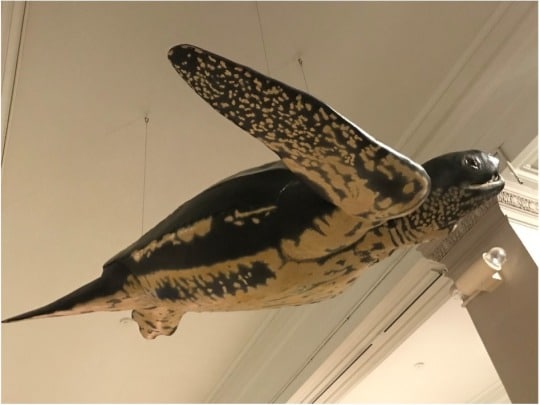

When people tour the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles, we make it a point to open one of the first metal tanks our guests see, tank 156. This tank houses a single impressive specimen – the giant head and esophagus of a leatherback sea turtle. I started as the collection manager of the section just under two years ago and, until recently, the only information I had for this specimen were the scant details noted in the section’s database and on a printed sheet attached to the lid of the tank: a fisherman had found the specimen dead when it washed ashore in Maine in 1965. That was it. I knew the entire animal (not just the head) had washed ashore since a cast was made of the body and that replica is now hanging in Discovery Basecamp. I also knew ecological and herpetological information about the species in general, but nearly every specimen in a natural history collection has a story, and I knew this one had to be good… but I didn’t know what it was…

… until I began digitizing the section’s archives.

Let’s take a step away from our leatherback sea turtle specimen to understand what “digitizing the section’s archives” really means. Carnegie Museum of Natural History is over 100 years old, and the herpetology archives date back to the museum’s inception. That means we had, at the time I became involved with the digitizing work, nearly 125 years of correspondence, field notes, specimen data, and collection-related events to clean, scan, and properly organize and house both physically and electronically. (For a more in-depth dive into this archiving process, see section archivist Ren Jordan’s post here.) It took a team of about 10 people (part-time and full-time interns, work-study students, and staff members) over a year to complete this daunting task. The treasure trove of information we unearthed in those archives is priceless, and CM 44460’s story is a treasure worth sharing.

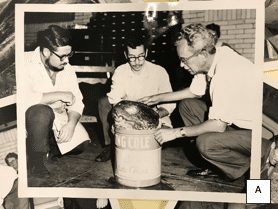

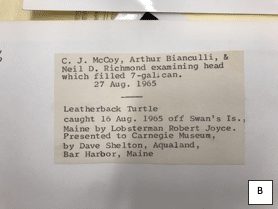

During the digitization work, the archival material I processed included the field notes of past-curator Dr. C. J. McCoy, and among his papers was a crumbly old folder labeled “CM 44460” that required rehousing. The number lacked any context for me at the time because the section has over 180,000 catalog (or CM) numbers and, try as I might, I don’t yet have them all memorized. When I pulled out pictures from the folder, though, CM 44460’s identity instantly became apparent, for I found myself looking at the images of our famous leatherback sea turtle. One picture showed the creation of the cast and another depicted the shell being carried by two men due to its size. Another image showed Dr. McCoy crouched with two other men near a huge open tin can labeled “Potato Chips” with, shockingly, the head of dear CM 44460 peeking out of the top. A note affixed to the back of the image read “C. J. McCoy, Arthur Bianculli, & Neil D. Richmond examining head which filled 7-gal. can. 27 Aug. 1965. Leatherback Turtle caught 16 Aug. 1965 off Swan’s Is., Maine by Lobsterman Robert Joyce. Presented to Carnegie Museum by Dave Shelton, Aqualand, Bar Harbor, Maine” (Image 4B). Suddenly pieces of the story were falling into place. This specimen was transported from Maine to Pittsburgh in pieces, with the head arriving separate from the body and shell in a 7-gallon potato chip container!

A couple months later, I unearthed another folder in the archives with data from the specimen. The documents recorded the preservation process of the turtle, including measuring and weighing different organs (knowing that they would be too large to properly preserve and store), and how long it took the head to become fully and properly fixed in formalin. Through these notes, I learned that the turtle was a female measuring 7’5” from the tip of her tail to the tip of her snout, and that her ocean wandering was powered by a flipper-span of 8’4”! Based upon her carapace (the top part of a turtle shell) measuring in at 5’5”, this turtle was likely sexually reproductive and, therefore, rather old. CM 44460’s story is so much clearer now and really goes to show how each specimen in a collection has its own unique history just waiting to be investigated.

Stevie Kennedy-Gold is the collection manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is a pitfall trap (for herpetology)?