by Amanda Martin

With Autumn upon us, temperatures are dropping, and it is getting colder out. Especially in the northern regions, amphibians and reptiles need to prepare for brumation (essentially, hibernation for ectotherms). Ectotherms like frogs, salamanders, snakes, and turtles are highly sensitive to changes in their environment and need to stay warm by actively moving in and out of areas with heat. When temperatures increase, ectotherm metabolism increases, and when temperatures go down, so does their metabolism. But how do they survive during winter, won’t they freeze?

Many snakes, like eastern garter snakes (Fig. 1) find shelters called hibernacula and curl up inside, sometimes intermixed with other snake species. These hibernacula are often small mammal burrows, dens, or tunnels below the frost line. During winter, typically between October and March, several hundred individuals will gather in the same den, tightly coiling their bodies together to stay warm enough to survive. They stop eating during this period because it is too cold to properly digest food and will stay hydrated by absorbing moisture through their scaly skin. Even though snakes are awake and sluggishly active, they expend very little energy during this time and do not lose much weight.

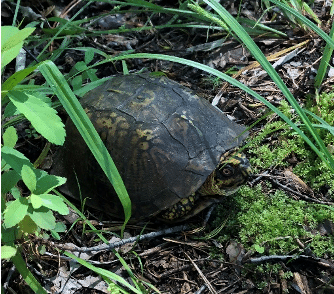

Turtles, on the other hand, are a bit different. Aquatic turtles survive winter underwater, and the terrestrial eastern box turtle (Fig. 2) buries itself underground by digging into the soil. One extreme overwintering survivor is the painted turtle, which spends most of its time in ponds and slow-moving freshwater. When these ponds freeze, painted turtles bury themselves up to 45 cm (nearly 18 inches) in mud beneath the pond’s surface. Amazingly, these turtles can survive for months in low or no oxygen environments. During warmer months, they breathe air, but when submerged for overwintering they absorb oxygen through the thin skin of their cloaca, a phenomenon called cloacal respiration.

Another amazing overwintering feat is the freeze tolerance of wood frogs (Fig. 3) which can become frogsicles! Wood frogs are unable to bury themselves completely, like turtles, so part of their body is often exposed when trying to stay underneath the mud. This is beneficial for obtaining oxygen through their skin. However, they still need to avoid freezing and will move around to warmer areas as needed. Many frogs stay in burrows or under leaf litter to escape the frost, but wood frogs will stay at shallower depths because they have high concentrations of glucose, which produces an “antifreeze” effect. This protects their organs when over two-thirds of their body freezes!

Other amphibians, like salamanders, do not have freeze tolerance like the wood frog. Red-backed salamanders (Fig. 4) are one of the most abundant species in the eastern United States. They are typically found underneath logs and leaf litter at shallow depths, but during winter when temperatures drop below 30°F, they travel as much as 15 inches under the ground in animal burrows. Other species, like spotted salamanders, will also look for deep burrows that are below the frost line.

In early spring when temperatures warm, amphibians and reptiles emerge from overwintering to look for basking sites, sunny spots to warm themselves. With warmer temperatures, the prey of many of these species also become more available. Garter snakes will look for slugs, earthworms, amphibians, minnows, and rodents, for example, and red-backed salamanders will eat a wide variety of invertebrates, such as spiders, worms, snails, and insects. The exact timing of emergence for amphibians and reptiles depends on a given year’s weather, resulting in variable emergence times from year to year that correspond to temperature. Not every individual makes it to the spring, but it is amazing that species that are so dependent on the temperature of their environment are capable of surviving up north!

Written by Amanda Martin, Post-doctoral Researcher in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Edited by Jennifer Sheridan, Assistant Curator in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

An Illuminating Tale of Tracking Turtles

How to Catch 311 Amphibians in 10 Days

Pitfall Traps: Fieldwork Surprises

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Martin, AmandaPublication date: September 14, 2020