by Amy Henrici

Collection managers at Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) typically spend their time on collection-based tasks. Sometimes, however, we are called on to clean out the office of a former curator in our respective sections. With the death of Section of Vertebrate Paleontology (VP) Curator Emerita Mary Dawson late last year, I’ve been spending time in her office sorting through numerous items she accumulated during her nearly 58-year career at the museum. While there, I can’t help but think of a conversation we had in her office many years ago when I expressed interest in obtaining a Master of Science degree in geology and paleontology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Mary agreed to be my advisor and suggested fossil fishes as a topic for my thesis, because at that time not many paleontologists were studying this group. She arranged for me to join a field crew from our Section led by curators Kris Krishtalka and Richard Stucky who planned to spend the summer of 1984 searching Eocene sediments (~56–34 million years ago) in the Wind River Basin of central Wyoming for fossils of mammals and other vertebrates. She instructed them to take me to the north end of Lysite Mountain, where during a 1965 reconnaissance geologist Dave Love (of the United States Geological Survey [USGS]) and his student Kirby Bay and others showed her some fish fossils.

As planned, in late June I set out from Pittsburgh in my un-airconditioned car on a three-day drive to Wyoming to join the crew who had arrived before me. Some of my time in the field was spent assisting the crew in their search for mammal fossils, something I had no experience with. My previous field work involved collecting ancient amphibian, reptile, and dinosaur fossils from the time before most mammals had evolved. Indeed, the first set of “fossils” that I collected on this trip turned out to be fragments of modern rabbit bones that Kris unceremoniously dumped into his ashtray while identifying the day’s haul after dinner. Fortunately, my skills at finding mammal fossils improved.

After a few days we went on the first of several reconnaissance trips to Lysite Mountain, which lies north of the Wind River Basin and forms part of the southern escarpment of the Bighorn Basin. To get there we drove deeply rutted and sometimes rocky dirt roads. Once there, the crew spread out in search of fossils. While some of us searched for and found incomplete and disarticulated fish fossils, others discovered a unit that produced frog fossils. When Kris and Richard showed me the frog fossils, they strongly urged me to base my thesis on the frogs instead of the scrappy fish I had collected. I quickly agreed, which was a decision that I never regretted.

We returned to our routine of prospecting for fossils in the Wind River Basin, until the planned arrival of Pat McShea (now my husband and Program Officer in the CMNH Department of Education) via a Trailways bus. The original plan was for Pat and me to drive my car daily to Lysite Mountain, but this was not feasible, given the condition of the roads. Instead the crew dropped us off with our camping gear for four days of fossil frog collecting. This was followed by a second field season in 1986, in which my sister, Ellen Henrici, joined us with her off-road capable SUV.

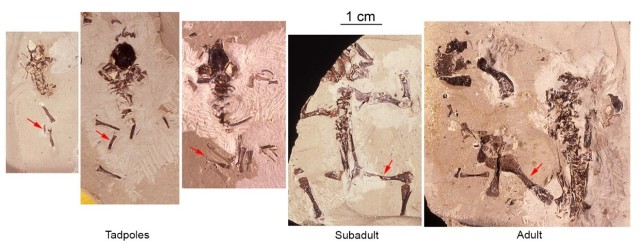

Using a hammer and chisel to pry open pieces of rock, we collected nearly 150 specimens of frog fossils in varying degrees of completeness. The preparation of the fossils and the identification of the various bones took me a long time. I eventually figured out that they were all the same type of frog and represented a new genus and species in the family Rhinophrynidae, which today is known by a single species: Rhinophrynus dorsalis, the Mexican burrowing toad. The fossil collection even includes tadpoles in various stages of development, as well as a mortality layer preserving the scattered bones of many individuals. I named this new genus and species Chelomophrynus bayi in a 1991 paper published in CMNH’s scientific journal, the Annals of Carnegie Museum.

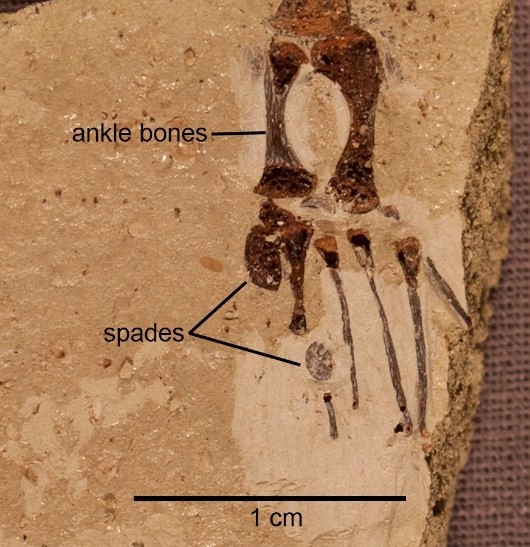

In paleontology, the study of living creatures can inform our understanding of fossils. The Mexican burrowing toad is very unusual in that it spends most of its life underground and only emerges to breed after heavy rain. The species currently inhabits dry tropical to subtropical forests along coastal lowlands in extreme southern Texas southward into Mexico and Central America. It has two bony spades on each hind foot that help it to efficiently dig, hind feet first, into the ground. Once underground, other skeletal specializations enable it to use its front feet and nose to penetrate termite and ant tunnels and then protrude its tongue into the tunnel to catch insects. Chelomophrynus possesses a number of these specializations (though some are not as well developed as in the modern Rhinophrynus), which strongly suggests that it too was able to burrow underground to feed on subterranean insects.

Rhinophrynids once occurred as far north as southwestern Saskatchewan, Canada around 36 million years ago. Their southward retreat to their current range could be because they apparently never developed the ability to hibernate in burrows, which would have protected them from seasonal sub-freezing temperatures which began developing around 34 million years ago.

The oldest rhinophrynid is Rhadinosteus parvus, a frog that lived with dinosaurs. In 1998, I was able to name and describe it based upon several late-stage tadpoles collected earlier from Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, a site where many of the dinosaurs on exhibit in CMNH came from. A cast of Rhadinosteus is displayed in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time gallery.

Amy Henrici is the Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to share their unique experiences from working at the museum.

Related Content

Super Science Saturday: Scientist Takeover (September 25, 2021)

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part I: Introduction and History

Fossil Matrix Under the Microscope

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Henrici, AmyPublication date: September 17, 2021