Last January, we started out hopeful for 2020, but unfortunately it ended up being a very difficult year for almost everyone. After an equally challenging start to 2021, I think it is safe to say our attitudes toward this year are more guarded, but nonetheless brave. We know that more hard times might be approaching, but if we could make it through 2020, we can make it through its successor. It is in this spirit that this edition of Mesozoic Monthly features Dreadnoughtus schrani, a colossal sauropod dinosaur whose genus name literally means “fearer of nothing.”

Dreadnoughtus has many connections to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH). Starting in 2005, a team that included CMNH’s own Dr. Matt Lamanna collected the only known fossil skeletons of the ginormous species in Santa Cruz Province of southern Patagonia, Argentina. Matt was also one of the authors of the paper that officially named the beast in 2014. Furthermore, many of the bones were scientifically prepared by staff and volunteers in the museum’s on-exhibit fossil lab, PaleoLab. Preparation involves freeing the fossils from the rock in which they were preserved (called matrix) using special tools, and then gluing/reinforcing the fossils back together as needed. Next time you visit CMNH, make sure to take a peek in PaleoLab to see our preparators in action!

Sauropod dinosaurs such as Dreadnoughtus are easily recognized by their frequently huge size, long necks, and long tails. CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time (DITT) exhibition features real fossil skeletons of three different sauropods: Camarasaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus. Brachiosaurus, one of the stars of Jurassic Park, is also a sauropod, and is featured in the mural in the Jurassic Period atrium in DITT.

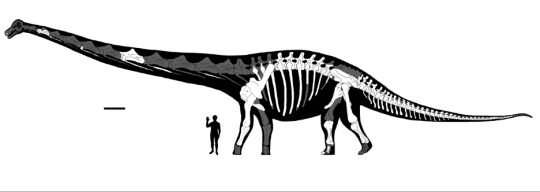

Dreadnoughtus belongs to a group of sauropods called titanosaurs that lived during the following Cretaceous Period, largely in the Southern Hemisphere. Titanosaurs have many interesting features that make them unique, such as simplified front feet with very few bones, extra-wide shoulders and hips, and even (in some species) bony plates called osteoderms embedded in the skin. However, as their name implies, titanosaurs’ primary claim to fame is their generally titanic size. Many titanosaurs were absolutely enormous – the smallest members of the group, such as Magyarosaurus, were outliers likely produced by insular dwarfism, a phenomenon in which typically large-bodied animals evolve smaller sizes that are more sustainable in geographically restricted habitats such as islands. Magyarosaurus lived in what’s now the Transylvania region of Romania, which was part of an island at the end of the Cretaceous. In contrast, Dreadnoughtus, which lived in prehistoric South America, was not restricted by an island habitat, and grew to an estimated 85 feet (26 meters) long. And, based on studies of the microscopic internal structure of its bones, it’s possible that the already-immense name-bearing specimen wasn’t even done growing before it died!

As you can imagine, it’s very hard to determine how much a dinosaur would have weighed when it was alive, especially for a dinosaur as large as Dreadnoughtus! Although multiple methods for calculating the weight of an extinct animal have been proposed, one of the most commonly employed techniques is volumetric mass estimation. Paleontologists using this method work with typically incomplete skeletons to first estimate how much of each type of tissue (like muscle or fat) covered the skeleton; afterward, they calculate how much each tissue type (including bone) weighed. It’s a difficult, somewhat speculative process that can result in different researchers producing wildly different estimates for the same animal’s weight. Estimates for Dreadnoughtushave been anywhere between 24.4 and 65.4 US tons (22.1 and 59.3 metric tons), but the most recent estimate was 54.0 US tons (49 metric tons). For comparison, a typical school bus weighs around 12.5 US tons (11.3 metric tons)! Clearly, no matter how you estimate it, Dreadnoughtus was a massive animal.

Gargantuan size has its drawbacks, but it also brings enormous benefits. It takes an absurd amount of resources to grow this large and power the organs needed to support life. However, if enough food is present to sustain this growth, predators are no longer an issue. Not even the largest meat-eating dinosaurs could pose a threat to something as large as an adult Dreadnoughtus. The only chances predators had to taste this sauropod were to hunt it when it was a small juvenile or to scavenge it when it was dead or dying. That seems to be what happened, too, because teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs were found scattered around the fossils.

So, as we continue our journey through 2021, let us think of ourselves like the unassailable Dreadnoughtus: the challenges of 2020 helped us to grow tremendously resilient, and the trials coming our way will not fracture our resolve. Times may be hard, but we are gigantic dinosaurs with no natural predators. We can do this.

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Dippy in Star Wars? The Krayt Dragon