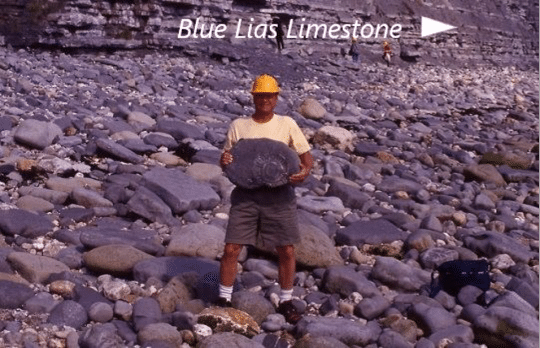

Two hundred million years before the birth of Mary Anning, a village in southeast England known as Lyme Regis, (Figure 1) was a shallow, watery world filled with pointy toothed reptiles, fish, and an abundance of ammonites. By 1799, the year of Mary’s birth, these ancient seas that deposited lime, silt and mud, had long receded, but evidence of the watery past remained in the Lyme Regis limestone and mudstone cliffs. Today, this region is part of a geologic formation of early Jurassic age known as the Blue Lias.

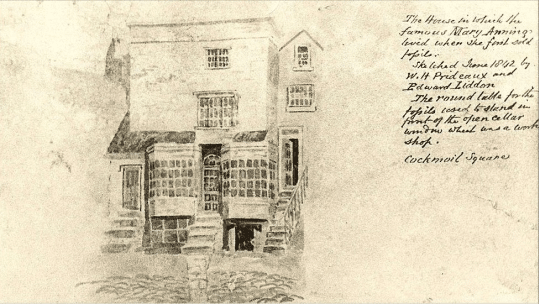

Mary’s father, Richard Anning, hunted fossils along the Lyme Regis coast to supplement his meager carpentry income. Mary and her brother, Joseph, accompanied their father along the landslide prone cliff in search of fossils to collect and sell to wealthy patrons and the scientific community. When she was 11, Mary’s father died of tuberculosis. His death left Mary, her mother and brother destitute. Despite the loss, they continued the family fossil business. At the age of 12, just one year after her father’s death, Mary excavated and identified the first ichthyosaur. Although Mary had no formal education and received no formal recognition for her monumental find, word of her abilities spread in the male dominated paleontological community. By the 1820’s, she managed the family fossil shop (Figure 2), a business where survival depended on finding major new specimens. At the age of 24, Mary uncovered the first plesiosaur skeleton and just five years later, the first pterosaur discovered in England.

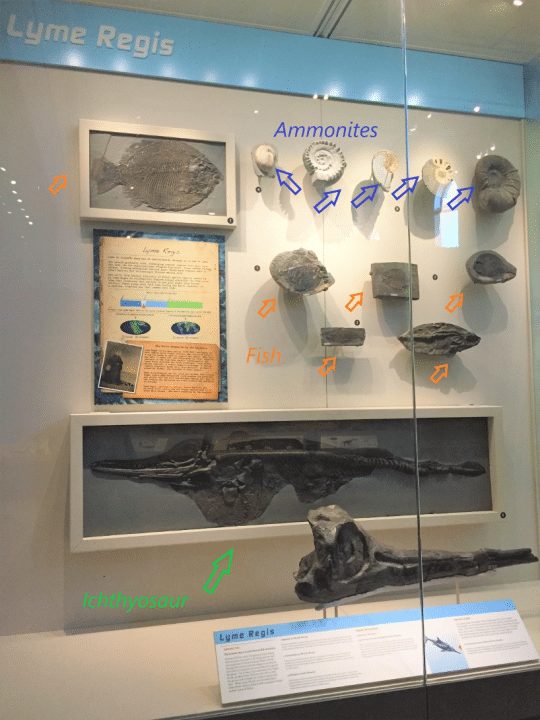

Visitors to Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition can scrutinize fish scale sized details in fossils from the Lyme Regis cliffs, an extraordinary level of preservation that Albert Kollar witnessed in the field when he collected fossils from the locality in 1999. (Figure 3).

A new movie, titled “Ammonite,” staring Kate Winslet as Mary Anning, promises to captivate a new generation with this often-overlooked chapter in the history of paleontology.

Despite hardship, lack of recognition, and danger, Mary continued working until her death from breast cancer in 1847. Her contributions to science were not formally recognized for over a century. In 2010, the Royal Society of London named her “one of the ten most influential women scientists in British History”

In a recent CMNH blog post, William Vincett, University of Delaware graduate student and Collecting Assistant for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, wrote, “It’s easy to see how she developed a love of fossils after discovering such a magnificent creature as a child.” Yes. Mary wondered, suffered, and persevered for the love of the Blue Lias.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter for the Department of Education and volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Thanks to author Barry Alfonso for thoughtful insight. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

The Hidden Fossil Treasures of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology