One of my favorite taxidermies in the Section of Mammals, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, is our groundhog with a malocclusion. Say what?

So, in dentistry, a malocclusion is the imperfect positioning of teeth when the jaws are closed, usually a cosmetic issue. If you are a rodent, like our groundhog, a malocclusion is not just cosmetic, but life threatening.

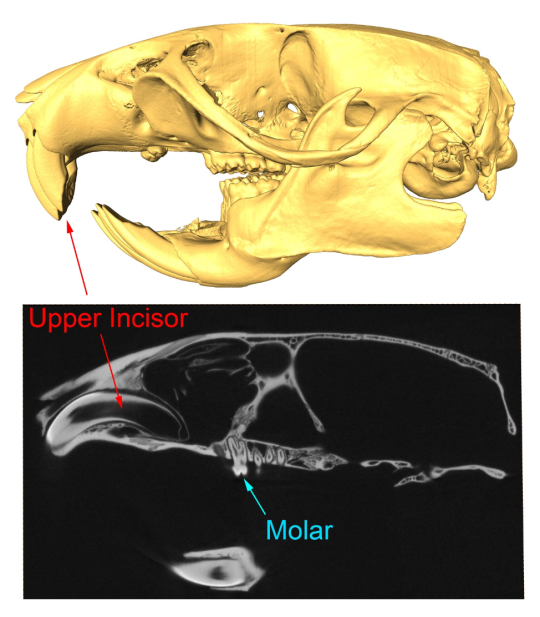

Rodents (including squirrels, beavers, rats, guinea pigs, and capybaras) are the most successful group of living mammals, accounting for about 40% of all species (2,500 out of 6,000). A key innovation that has led to their evolutionary success is their pair of enlarged upper and lower incisors that continue to grow during the life of the individual. Looking at a rat skull (below), you will notice that the incisors are enormous, especially compared to a molar tooth in the CT scan. When the upper and lower incisors occlude (that is, contact), over time they create a sharp, chisel-shaped cutting blade that is, for example, the reason a beaver can cut down a sizeable tree. Their incisors continue to grow and maintain that cutting blade. In contrast, your teeth don’t grow (nor do the molars of the rat or groundhog); in fact, they get smaller as they wear down.

If something goes awry with a rodent’s incisors such that the uppers and lowers get off kilter and don’t meet to create that cutting blade, the incisors will still continue to grow, and grow, and grow, as with our poor maloccluded groundhog. Ultimately, the animal will be unable to eat and starve to death. Ironic that the key innovation leading to the success of the rodent lineage can also be deadly for an individual on the rare occasion that things go wrong.

Rattus norvegicus, brown (Norway) rat, skull in lateral view (above) with sagittal section from CT scan (below).

John Wible, PhD, is the curator of the Section of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. John’s research is focused on the tree of life of mammals, understanding the evolutionary relationships between living and extinct taxa, and how the mammalian fauna on Earth got to be the way it is today. He uses his expertise on the anatomy of living mammals to reconstruct the lifeways of extinct mammals. John lives with his wife and two sons in a house full of cats and rabbits in Ross Township.