The first herbarium I visited was the Pringle Herbarium at the University of Vermont as part of an undergraduate class on plant taxonomy and systematics. Prior to this visit, I assumed herbaria were fairly mundane collections of dead, dry, flattened plants, and that they couldn’t possibly interest me as much as emerald-green plants thriving in the wild. However, within moments of entering the Pringle Herbarium, I was captivated by the football-sized cones of the sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana). These giant cones, of a species native to mountain slopes in California and Oregon, were the largest of any gymnosperm I had seen at that time, and I quickly discovered that herbaria were fascinating resources for studying plant diversity around the world.

Years later as a graduate student interested in plant functional ecology, I was reminded of the diversity contained within herbaria, but learned that herbarium specimens were rarely used to study plant functional traits. Functional traits are characteristics that provide ecologists with information about growth, reproduction, or survival strategies, and in plants they are often measured using living tissue. For example, three commonly measured functional traits are specific leaf area, wood density, and leaf thickness. Specific leaf area (equal to the fresh area of a leaf divided by its dry mass) indicates how much dry mass plants invest in their leaves, a factor coordinated with their rate of photosynthesis. More specifically, plant photosynthetic rates tend to increase the bigger leaves get relative to their dry mass. On the other hand, wood density is used to understand carbon storage, which is important for studying carbon sequestration and climate change. Leaf thickness can help understand leaf thermoregulation, herbivory, and gas exchange. Currently, it’s unclear if herbarium specimens can provide reasonable estimates of these traits, but if so herbaria can vastly expand our understanding of plant functional diversity.

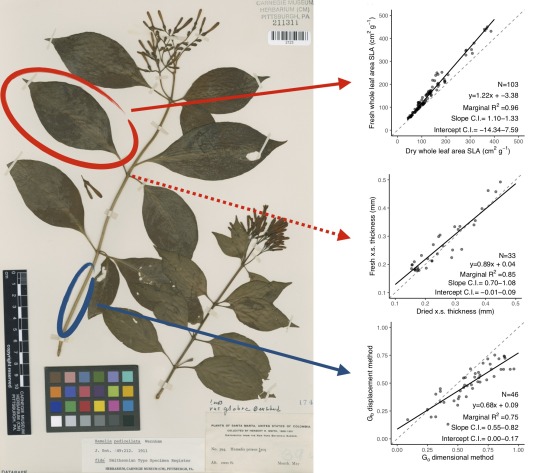

Recently, I teamed up with scientists Jessica Rodriguez and Dr. Mason Heberling (Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History) to understand if and to what extent herbarium specimens could be used as proxies for functional traits collected from fresh plant tissues. In our study just published in the American Journal of Botany, we found that herbarium specimens can provide accurate estimates of specific leaf area, branch wood density, and leaf thickness. Although drying plant tissues may lead to some inaccuracies in functional traits that are typically measured using fresh tissues, our study suggests the dead, dry, flat plants I once considered uninteresting could rapidly advance what scientists know about plant functional diversity. Importantly, our research highlights herbaria as rich sources of functional trait data with the potential to accelerate the study of important ecological processes like species responses to climate change.

Timothy M. Perez, Ph.D. is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of British Columbia whose research focuses on plant heat tolerance and the conservation of plants in the tropics.

Related Content

The Circle of Life…and Invasion