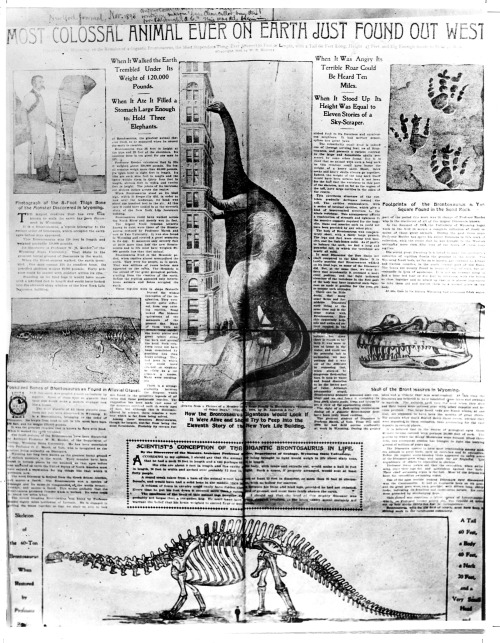

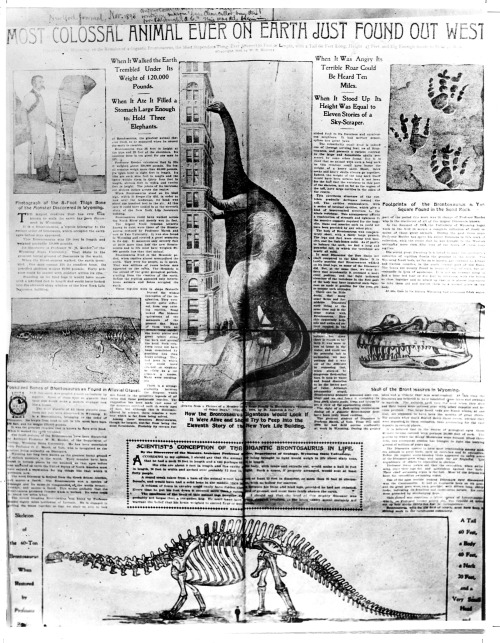

In 1898, Andrew Carnegie sent this newspaper clipping to Carnegie Museum of Natural History Director Dr. William J. Holland with a $10,000 check and a note that read, “buy this for Pittsburgh.”

Carnegie Museum of Natural History

One of the Four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

by wpengine

In 1898, Andrew Carnegie sent this newspaper clipping to Carnegie Museum of Natural History Director Dr. William J. Holland with a $10,000 check and a note that read, “buy this for Pittsburgh.”

by wpengine

T-Rex teeth in Dinosaurs in their Time at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

(Photo by Josh Franzos)

by wpengine

This immature Camarasaurus’ uncomfortable stance isn’t caused by a crick in his long neck. It was discovered in what paleontologists call the “death pose.” Many dinosaur skeletons like this one are found with their neck arching back dramatically towards the tail. This specimen in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time is displayed almost exactly as it was discovered.

The death pose may have been caused by the dinosaur’s final thrashing movements before it died. Scientists note that this pose is only seen in animals with high metabolic rates, suggesting that dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus may have been active creatures.

by wpengine

The most amazing thing about the skeletons in our Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibit is that the majority of their bones are the real deal.

The second most amazing thing about those skeletons is that whenever a bone was missing, someone had to create a cast of that bone from scratch.

Dan Pickering is one of those craftsman. Dan, whose been part of the museum’s PaleoLab team since 2005, is an artist, a sculptor by training.

He first used his skills in the exhibit department, but when the overhaul of Dinosaur Hall and its inhabitants became a reality, as Dan puts it, “I wanted a piece of the dinosaur action.”

Pictured above: Dan preparing a giant neck vertebrae of Dreadnoughtus, a super-massive dinosaur from Patagonia excavated and studied by museum dinosaur hunter Matt Lamanna and colleagues.